NFL 101: Introducing the Basics of the Two-Minute Offense – Bleacher Report

In this installment of Bleacher Report’s “NFL 101” series, former NFL defensive back Matt Bowen breaks down schemes and execution for the two-minute offense at the pro level.

Click here for the previous version of NFL 101, which broke down the prevent defense.

The two-minute offense in the NFL has multiple variations of personnel, alignment and play-calling, but the basic strategy (or philosophy) doesn’t change between teams when you turn on the tape.

This is an up-tempo playbook, one that leans on sideline throws, the screen game, spread runs and three-level route concepts to move the ball—quickly—into scoring position with quarterbacks running the show at the line of scrimmage in a no-huddle system.

With two-minute scripts predicated on game situation (timeouts, clock management), NFL offenses look to start with the screen or draw before creating throwing windows into the boundary along with opportunities to get the ball to their playmakers in open space.

Using examples from the All-22 coaches tape, let’s break down some basic concepts you need to know when the clock starts to tick at the end of the half—or during a game-winning situation—in the two-minute drill.

Screen and Draw

From a defensive perspective, the screen and draw should be alerted immediately when you take the field in a two-minute situation. This is the first call—the safe call—that pro offenses use to jump-start their two-minute game plan.

Why start with the screen or draw? Think of the possible prevent look you can see from the defense (defenders gaining more depth, sinking hard at the snap) and the front-four philosophy. These defensive linemen and edge-defenders often see the two-minute drill as an opportunity to play pass first and rush hard up the field, with the protection of seven (or sometimes eight defenders) dropping into coverage.

That creates a situation where the offense can take advantage of the linemen and edge-defenders playing pass first with the screen or the draw to pick up a nice chunk of yardage to start the two-minute drill.

Here’s an example of the screen—a running back “slip” screen—from Raiders-Seahawks, with Marshawn Lynch producing an explosive gain.

With the left tackle setting deep (showing dropback pass versus the edge-defender) and both the guard and center inviting the defensive tackle to rush up the field, the Seahawks can slide Lynch to the open side of the formation.

That allows quarterback Russell Wilson to give ground and dump the ball off to Lynch with the linebackers dropping into coverage. That’s trouble for the Raiders.

This was the first play of the Seahawks’ two-minute drill, and it produced an explosive gain (40-plus yards) on a basic screen concept versus a defense that didn’t recognize or alert to the scheme.

Now, let’s check out the running back draw scheme from Chargers-Dolphins, with Miami producing a first down versus a 6-Man run box.

Start with the offensive tackles from the Dolphins. As you can see, they both show pass sets. This invites the edge-defenders to rush up the field. Inside, the second-level defenders hesitate instead of reading run and attacking downhill. This allows both the open-side guard and the tight end to work up to the second level to create a running lane for Lamar Miller.

This is another basic scheme—at the start of the two-minute drill—that moves the sticks or picks up some yardage with the offense ready to go on the next snap with one or two play calls in their back pocket.

“Spread” Runs

Along with the screen or draw, more and more NFL teams are leaning on the “spread” runs (or nickel runs) early in the two-minute drill to expose light run fronts and defenders dropping with speed into coverage (lazy run/pass keys).

These run concepts are usually shown out of one-back looks with offenses producing yardage on the zone scheme, one-back power, inside trap and even the read-option. Hey, if the defense is going to show a six-man front, then take advantage of the numbers and move the ball up the field.

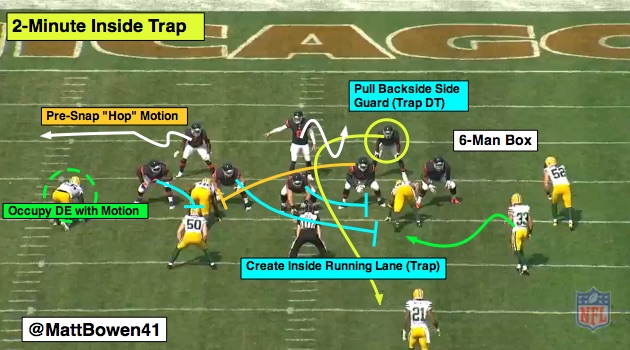

Check out the Bears’ inside trap scheme from their matchup with the Packers at Soldier Field.

Bleacher Report

The Bears added some window dressing on this scheme out of a split-back “pony” look (two tailbacks in the game) with Ka’Deem Carey on short “hop” motion to occupy the defensive end. However, even without the pre-snap movement, this is really a five-man front from the Packers with a safety dropping down late.

This sets up for the Bears to block down and pull the backside guard to trap the defensive tackle, thus creating a massive inside running lane for Matt Forte at the start of the two-minute drill.

Take a look at how the blocking scheme plays out with the trap action with the backside guard absolutely lighting up the defensive tackle:

In another example, the Saints use the inside zone scheme versus the Falcons to move the ball into positive territory with running back Pierre Thomas against an extremely light run front.

With the Falcons “moving” to a coverage look, quarterback Drew Brees can hand off to Thomas on the zone scheme, and the Saints have the numbers up front. This is smart call from the Saints as it allows the offensive front to step playside with Thomas finding a huge chunk of daylight to press this ball up the field.

Given the time limitations, the run game can often take a back seat in the two-minute drill. However, at the start of a series or after a dead ball, using the basic one-back schemes is an excellent way to expose prevent run fronts and pick up a nice gain on the ground.

Out, Comeback and Flat

As a defensive player, you know the ball is going to the sideline. That means you must prepare for outside cuts and pre-snap splits that tell a story.

The majority of route combinations will include a flat option for the quarterback. If you want to take away the middle of the field and the deep sideline windows, then the ball is going underneath, and there will be a foot race to the sideline with a tight end or running back releasing to the flat.

However, the two most common routes in a two-minute drill are the comeback and out from the single-receiver side. Think of Antonio Brown, Demaryius Thomas, Dez Bryant or Jordy Nelson. That’s where the ball is going, and it’s all based on the split and release.

On the comeback, look for a split wide of the numbers with an outside release. There are only two routes run from that split and release: fade or comeback. And the idea here is for the wide receiver to push the cornerback up the field (sell the fade) before snapping back downhill to the comeback at a depth of 12-15 yards. Make the catch, step out of bounds and move the ball.

With the out route, it’s all about creating room for the wide receiver. If he aligns on top of the numbers, it’s an automatic alert for the out. But if he is on the bottom of the numbers, play for the inside stem (back to the top of the numbers) to create more space to break back to the sideline.

Here’s the out route from Brown versus the Saints’ “Thumbs” technique (cornerback over the top, safety buzzing underneath).

Check out the stem from Brown as he pushes inside to the top of the numbers. That will create more space for the Steelers wide receiver at the break point to separate from the cornerback while giving quarterback Ben Roethlisberger a clear window to target the outside breaking cut.

This is just one example, but turn on any game and you’ll find a ton of out routes and comebacks in the two-minute drill versus man-coverage. This is how you pick up a quick 15 yards, stop the clock and give your offense a chance to huddle up on the field.

How do you stop it? Keep your leverage as a defensive back. There is no help outside when the free safety is hanging out in the middle of the field.

Deep Sideline Combination Routes

Staying with the sideline throws, let’s talk about two route combinations that show up often in the two-minute drill because they can beat man coverage, Cover 2 and Cover 3 by setting some underneath bait to open up a deep window on the sideline.

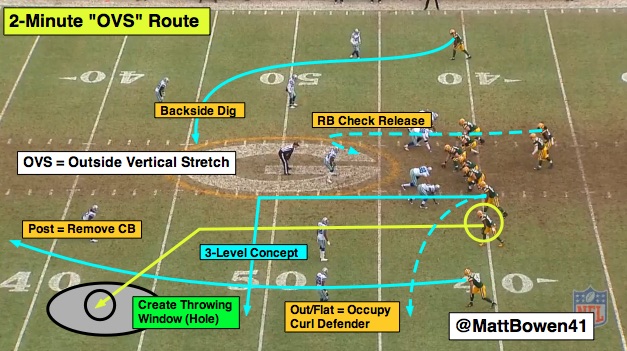

The first is the “OVS” or “outside vertical stretch” combination. This is a three-level route designed to clear-out the top of the defense while forcing the underneath defender to bite on the flat or quick out route. This allows the offense to target the deep 7 cut (corner) route into the boundary.

Take a look at the Packers “OVS” concept from the divisional round matchup versus the Cowboys at Lambeau.

Bleacher Report

With the Cowboys playing a three-deep zone shell (3 Buzz), the Packers can clear-out the cornerback (and occupy the free safety) on the post (Jordy Nelson), run the tight end on the quick out and target the 7 cut (Randall Cobb) once the curl defender sits (or squats) underneath.

That creates the open window for quarterback Aaron Rodgers to target Cobb on an outside breaking cut which allows the wide receiver to make the grab, step out of bounds and pick up an explosive gain while stopping the clock.

Check out the play below and focus on the curl defender fails to get depth (sinks to the out route). That’s all it takes for Cobb to find the vacated spot in the zone while Nelson pushes the cornerback down the field.

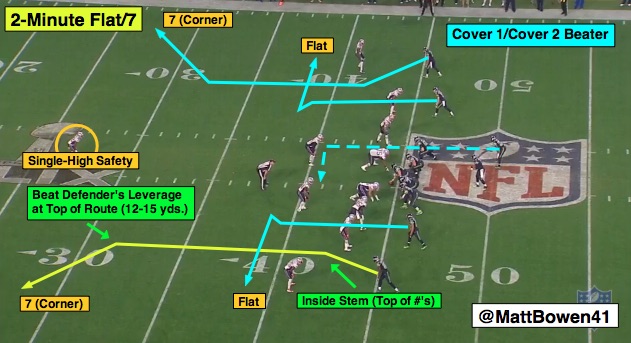

The next route is the classic flat-7 (corner) combination. This is one of the top Cover 2 beaters in the NFL as the flat route sets the bait for the cornerback with the 7 cut breaking in front of the deep half safety (remember, the safety is taught to play top-down here). If the cornerback squats on the flat (instead of sinking under the 7 route), NFL quarterbacks will light up Cover 2 on this combination.

Plus, this is also a route NFL offenses can run versus man-coverage to force the cornerback to maintain his leverage on a route breaking away from the safety help in the middle of the field.

Back in the Super Bowl, Russell Wilson and the Seahawks used the flat-7 route to pick up an explosive gain at the end of the half versus the Patriots’ Cover 1 look (man-free) to set up an eventual touchdown.

Bleacher Report

With the No. 1 wide receiver aligned outside of the numbers, he has to take a hard inside stem to the top of the numbers (create room to the sideline) and break at a depth of 12-15 yards.

These are only two of the many route combinations NFL offenses use at the end of the half to work the sideline, but both are at the top of the call sheet for multiple teams because they create two- and three-level reads for the quarterback with concepts that break into the boundary.

Secure the catch and get out of bounds.

“Run After the Catch” Route Combinations

Inside crossing routes, the slant-combination, the Hi-Lo series, etc. During two-minute drills, offenses will scheme to get the ball into the hands of their playmakers. That means more “rub” routes, bunch alignments and three-step concepts that allow the quarterback to target receivers (and backs) with space in front of them.

If offenses have time on the clock (or a couple of timeouts in their back pockets), they can make high-percentage throws inside of the numbers that create opportunities for receivers after the catch. Unlike the outside breaking cuts we talked about above (catch and step out of bounds), these routes generate situations where receivers can get up the field or pick up more yardage before eventually stepping out of bounds.

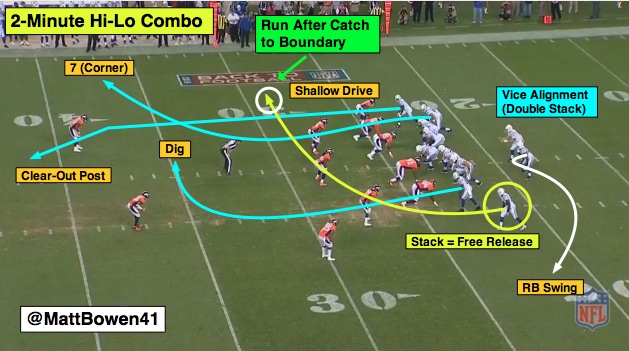

This is the Colts’ Hi-Lo concept (two-level read) from their Week 1 matchup versus the Broncos with a clear-out to the front side and a receiver running the shallow cross underneath.

Bleacher Report

This creates an easy throw for quarterback Andrew Luck to target wide receiver Hakeem Nicks on the shallow drive route, with T.Y. Hilton and Coby Fleener clearing out the front side of the formation.

Nicks makes the grab here, gets up the field and picks up a quick 10 yards before ducking out of bounds to stop the clock.

Looking at the slant-flat, this is one of the most basic combinations (at every level) of the game—a three-step route with the quarterback reading to the slant or the flat versus both zone and man-coverage.

In a two-minute drill, this route combination gives the quarterback the option of throwing the flat (boundary route) or targeting the slant depending on the clock situation. And the slant route can be lethal versus man-coverage if the wide receiver creates enough separation to get the ball in space after the catch.

Here’s an example from Patriots-Packers, with Jordy Nelson working versus Darrelle Revis in a man-coverage alignment:

With Nelson winning to the inside on Revis (playing from an outside shade) and free safety Devin McCourty taking a poor entry angle to the ball from his middle-of-the-field alignment, the Packers wideout can take a three-step route and turn it into an explosive gain and a score at the end of the half.

These route combos don’t have to be complicated when playmakers get their hands on the ball during a two-minute situation. Give them room to work with, and let them create in the open field.

End-Zone Throws (Red Zone)

As a standard rule, the quarterback is going to target the end zone in a two-minute drill once the ball moves inside of the 20-yard line—especially if the clock comes into play.

This is where the defense should play for four verticals, the 7 cuts, the inside seam, etc. I’m talking about throws that preserve time and avoid dumping the ball underneath where the receiver can be tackled in bounds. In a red-zone situation, defenses are going to guard the boundary, so look for middle of-the-field throws into the end zone, and avoid targeting the flat.

Check out this example from the Dolphins-Broncos matchup with Peyton Manning targeting Demaryius Thomas on the “dino” post (quick double-move at the top of the route), as Denver has no timeouts left to work with.

With the Dolphins playing Cover 2 and the Mike ‘backer slow to drop, open and identify the route, Thomas gets a true one-on-one matchup versus a safety. This creates a situation where Thomas can sell the 7 route and then quickly break back inside to the post for six points.

Similar to a red-zone situation outside of a two-minute drill, the tight end position is going to come into play given the amount of Cover 2 that shows up on the tape, and the majority of the throws are headed into the end zone.

The “Checkdown”

I wanted to throw in the checkdown to the running back because we see it so often versus defenses that play extremely soft zone looks.

With defenders racing back to gain depth, the simple checkdown option can produce a 10-, 15- or even 20-yard gain versus a deep Cover 2 or Cover 4 look. This forces the underneath defenders to come back downhill, square up the ball-carrier and make a tackle in space.

Eventually, the offense will have to challenge the defense, but why not take the checkdown early in a two-minute drill if the defense is going to vacate 10-15 yards underneath?

Look at this example from the Bears-Lions matchup with Matthew Stafford dumping the ball down to running back Theo Riddick on the checkdown versus Cover 2.

This might seem like nothing, but at the end of the play, the Lions picked up 20 yards. That’s ridiculous and something that should never happen from a defensive perspective.

Bottom line: If the defense plays a true “prevent look,” then hit them underneath for a quick chunk of yardage.

The “Fake Spike”

Let’s wrap this up with the “fake spike” because it takes some guts to pull this off if the offense is truly in a critical game situation in the two-minute drill.

You remember the “fake spike” from Dan Marino and the Dolphins at the end of the Monday Night game versus the Jets in 1994? Check it out:

With less than 30 seconds left, Marino calls for the “spike” at the line but then throws the quick back-shoulder fade for six points. That’s one of the classic tosses in NFL history with the Jets thinking they could take a play off before Marino decided to win the game.

We saw a very similar play this past season at the end of the Packers-Dolphins game with Rodgers hitting Davante Adams on the quick hitch route off the “fake spike” that set up the game-winning touchdown pass.

I was in in plenty of situations during my time in the NFL when the quarterback “clocked” the ball with the spike, and you do relax a bit. Instead of getting low in your stance, reading the formation, alignment, etc., it’s easy to stand up tall and try to catch your breath. Just look at the defensive linemen and secondary in those clips. They aren’t expecting anything other than the quarterback slamming the ball into the ground.

But as both Marino and Rodgers showed us, you can never truly take a play off in a two-minute drill.

Seven-year NFL veteran Matt Bowen is an NFL National Lead Writer for Bleacher Report.

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service – if this is your content and you’re reading it on someone else’s site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.