Players' average salary now tops $4 million

Major League Baseball players make bank, as the kids say. The Associated Press did some figuring, and reported Tuesday that the average annual MLB salary in 2014 will surpass $4 million — a princely sum, and also a record. In 1976 when free agency began, the average salary was about $50,000, or roughly $206,000 in today’s dollars when measuring against the consumer price index. And these certainly ain’t your grandfather’s ballplayers, who used to work during the offseason at second jobs in order to help make ends meet.

Players of today know they have it good.

“We’re enjoying a tremendously bountiful season in baseball,” said Toronto pitcher R.A. Dickey, the 2012 NL Cy Young Award winner with the New York Mets.

Fueled by the largest two-year growth in more than a decade, the average salary projects to be about $4.25 million, according to the AP study, with the final figure depending on how many players are put on the disabled list before the first pitch is thrown. That is up from $3.95 million on the first day of last season and $3.65 million when 2013 began.

“MLB’s revenues have grown in recent years, with the increase in national and local broadcast rights fees being a primary contributor,” said Dan Halem, MLB’s chief legal officer. “It is expected that player compensation will increase as club revenues increase.”

Yes, about those club revenues. Thanks in large part to rich local and national TV contracts that have tripled in recent years, MLB is a $9 billion industry, so even though a $4.25 million average player salary is a wonderful amount of money, league owners are getting off cheaply when it comes to payroll.

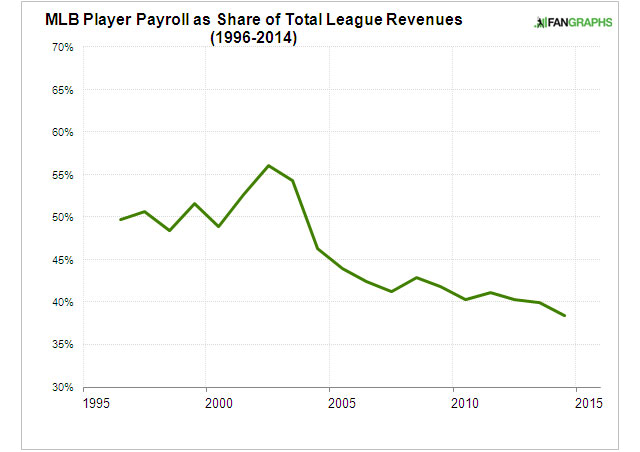

As this astute analysis by Nathaniel Grow of Fangraphs shows, the players share of the wealth in MLB has been in sharp decline for more than a decade:

(FanGraphs)

(FanGraphs)After peaking at a little more than 56% in 2002, today MLB player salaries account for less than 40% of league revenues, a decline of nearly 33% in just 12 years. As a result, player payroll today accounts for just over 38% of MLB’s total revenues, a figure that just ten years ago would have been unimaginably low.

If I’m an MLB player, reversing this trend is my number one priority heading into the 2016 CBA negotiations.

So that’s the downside to labor peace. Donald Fehr is spinning in his grave, and the man’s alive and well working for NHL players. Marvin Miller is just laying there, shaking his head. M.M. doesn’t spin.

Now, this is not a call for the MLBPA to hear the proletariat’s call and go out on strike, or that fans need to sell candy or have a scrap drive and give players the proceeds in order to supplement their waning incomes. It’s billionaires vs. millionaires, and many of you would just want to stay out of it and that’s fine.

All that’s being said is, the players are the sport and they’re getting the… short end of the stack of the gold bricks.

How do MLB players compare to the NFL and NBA? Grow in Fangraphs writes that all three unions got more than 50 percent of revenues in 2001, with MLB players getting the most. Today, all three are below 43 percent, with MLB players getting the least.

So, what’s been happening, other than illegal owner collusion, (which no one is alleging yet)? FanGraphs suggests the following are true:

• Owners have gotten smarter and more efficient — they’re not overpaying for older free agents as often.

• They’re signing their own players to team-friendly contract extensions that buy out arbitration and, in some cases, free-agency years.

• Revenue sharing and luxury tax penalties have lessened the incentive to spend on payroll.

• Payroll disparity between big-market and small-market teams has not changed appreciably in the revenue-sharing era. The Kansas City Royals and Pittsburgh Pirates haven’t closed the gap on the Yankees and Dodgers, for example.

As an astute baseball fan points out, many ownership groups aren’t simply pocketing the cash, or using it to buy a new fleet of yachts. Some are paying for their franchises, which have skyrocketed in value. And the biggest losers (you’re not going to believe this) are fans of teams like the Dodgers, made richer by local TV deals but who also don’t televise the games to most fans because of fees disputes with cable companies. Or fans who are made to pay more for games in order to subsidize the deals.

So, if you don’t want to wave the union flag for Tony Clark and the players, it’s understandable.

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service – if this is your content and you’re reading it on someone else’s site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.