WHEN LEBRON JAMES walks onto the court for tipoff against the Detroit Pistons, he might as well tug up his shorts, bend his knees and get in his defensive stance right away. James may not know it, and the millions watching may not know it either, but there’s almost no chance he’ll retrieve the ball on the opening jump.

That’s because just a few feet away, crouching at the center circle, stands jump-ball wunderkind Andre Drummond. The 22-year-old, despite standing shorter than a large portion of his jump-ball adversaries, has won 69.4 percent of jump-balls since he has been in the league. That’s an astounding figure that ranks as the best career rate among all active players and tops for every sub-7-footer on record, according to tracking by analytics site Nylon Calculus. Only 7-3 Arvydas Sabonis, 7-1 Shaquille O’Neal and 7-3 Zydrunas Ilgauskas have been more successful at winning the ball out of the air since this data became available in 1998.

This particular skill isn’t just about height. If it were, Yao Ming wouldn’t have a 43.2 career win rate. And it’s not just about having limbs for days either, or else Anthony Davis would check in higher than 39.5 percent.

What Drummond has, and others near-300 pounders lack, is freakish athleticism that allows him to reach towering heights faster than anybody. But that’s only the beginning of it. More to the point: What Drummond has worked to develop — including terrific reaction time and elite neuroprocessing — might be the most mechanically perfect body in the NBA.

And the science proves it.

A SIMPLE QUESTION is posed to Eric Leidersdorf, the lead biomechanist at the sports science lab P3 Peak Performance: How would you define athleticism in a single 140-character tweet?

The bearded Stanford-grad pauses as he sits at his desk in Santa Barbara, California. He launches into a lengthy monologue filled with scientific jargon, as if he were a modern-day Sir Isaac Newton. Phrases such as “kinematic quality,” “force generation capabilities” and “eccentric workloads” pour from his mouth.

After nearly a minute of expert technical explanation, Leidersdorf stops himself and begins to laugh.

“Or honestly, just be like Andre Drummond.”

More than 100 NBA big men have walked through the doors at P3 — a former disco dance hall nestled about a football field away from the shores of Santa Barbara — to get tested for their biomechanics and to optimize their movement patterns. None of them, according to P3’s scientists, walked out of there having checked more boxes on their assessment than Drummond.

“He checks off all the same boxes that the perimeter players do,” says Dr. Marcus Elliott, the founder and lead scientist at P3. “That’s super rare for a big man. You almost never have a guy that big who’s comparable to a 200-pound guy. There’s usually a give back.”

Stan Van Gundy, Drummond’s head coach and the Pistons’ president of basketball operations, had to see it for himself. As Drummond spent six weeks at P3 this past summer to train and get ready for his upcoming contract season, Van Gundy flew out and received a first-hand overview about what P3 was all about and what its technology had to say about his star player.

It was a pivotal summer for Drummond. The playoffs were within reach and so was an All-Star bid. Real dollars were at stake too. If Drummond stayed healthy and honed his craft, he would be in line for a potential max contract in the summer of 2016.

Van Gundy read the charts that detailed Drummond’s performance data. And what he learned was jaw-dropping.

“He checks off all the same boxes that the perimeter players do. That’s super rare for a big man. There’s usually a give back.”

Dr. Marcus Elliott, a lead scientist at P3

It’s not just that Drummond has a high vertical (30 inches) and generates more force in the vertical plane when he jumps than 90 percent of all P3 athletes. It’s not just that he moves laterally better than 87 percent of all NBA players tested — guards included. It’s not just that his second jump is lightning-quick and it rises four inches higher than his positional mean. The baffling thing? He does all of these things and more.

“Drummond has what we call a big jump vocabulary, meaning he can jump in a whole lot of different ways really well,” Elliott says. “We get some athletes who are amazing jumpers that are in a really limited setting. If things are set up just right for them, they’re freaks. Drummond will go off two legs, he’ll go off his right leg, left leg, right leg on an angle, left leg on an angle, all those things, he does it exceptionally well.”

Ask Drummond what stands out the most about his time at P3 and he immediately points to the stimulus-response test — when a P3 staffer holds two tennis balls, one in each hand, extended out to his sides like a uppercase “T.” The task for the athlete, who is facing the staffer a couple feet away, is to slide one meter laterally in the direction of the ball once it is dropped. But the athlete doesn’t know which ball will be dropped.

This task measures reaction time, force generated and speed — three critical barometers for an NBA athlete like Drummond. Simply put: When reacting to a visual stimulus, Drummond generates more force in the lateral plane, which helps to power his way through traffic than any other big man tested at P3. And he does it quicker than 91 percent of big men tested.

Andre Drummond — on the move!

Despite his 6-foot-11, 280-pound frame, Drummond is almost 14 percent faster moving one meter laterally, than the average NBA big man.

The numbers confirmed Drummond’s sneaky suspicion: He’s quicker than he is large.

“When I play, there are things throughout the game that I notice, especially rebounding,” Drummond says. “Not too many guys my size react as quickly.”

COACHES EVERYWHERE WOULD like you to believe that rebounding is all about oft-cliched intangibles such as heart, effort and grit. How did that guy get that rebound? He just wanted it more.

The hard truth is that most of rebounding, at least at the highest level, can be explained by pure biomechanics.

“Rebounding is something that just comes very naturally to him,” Van Gundy says. “He’s quick and he’s long and he can make multiple jumps. That’s a gift he has, and I don’t mean that to demean his effort at all, because obviously you have to make an effort to get those. But it’s not like he’s sitting around, focusing really hard, like, ‘I have to get 15 rebounds.'”

Van Gundy, who coached Shaq as an assistant coach in Miami and Dwight Howard as a head coach in Orlando, continues to marvel at Drummond’s ability to clean the glass.

“The thing that struck me is there would be games where you weren’t particularly impressed with either his effort or his production, so it didn’t seem like, ‘Wow, he’s everywhere.’ Then you pick up the stat sheet and you see he has 15 rebounds.

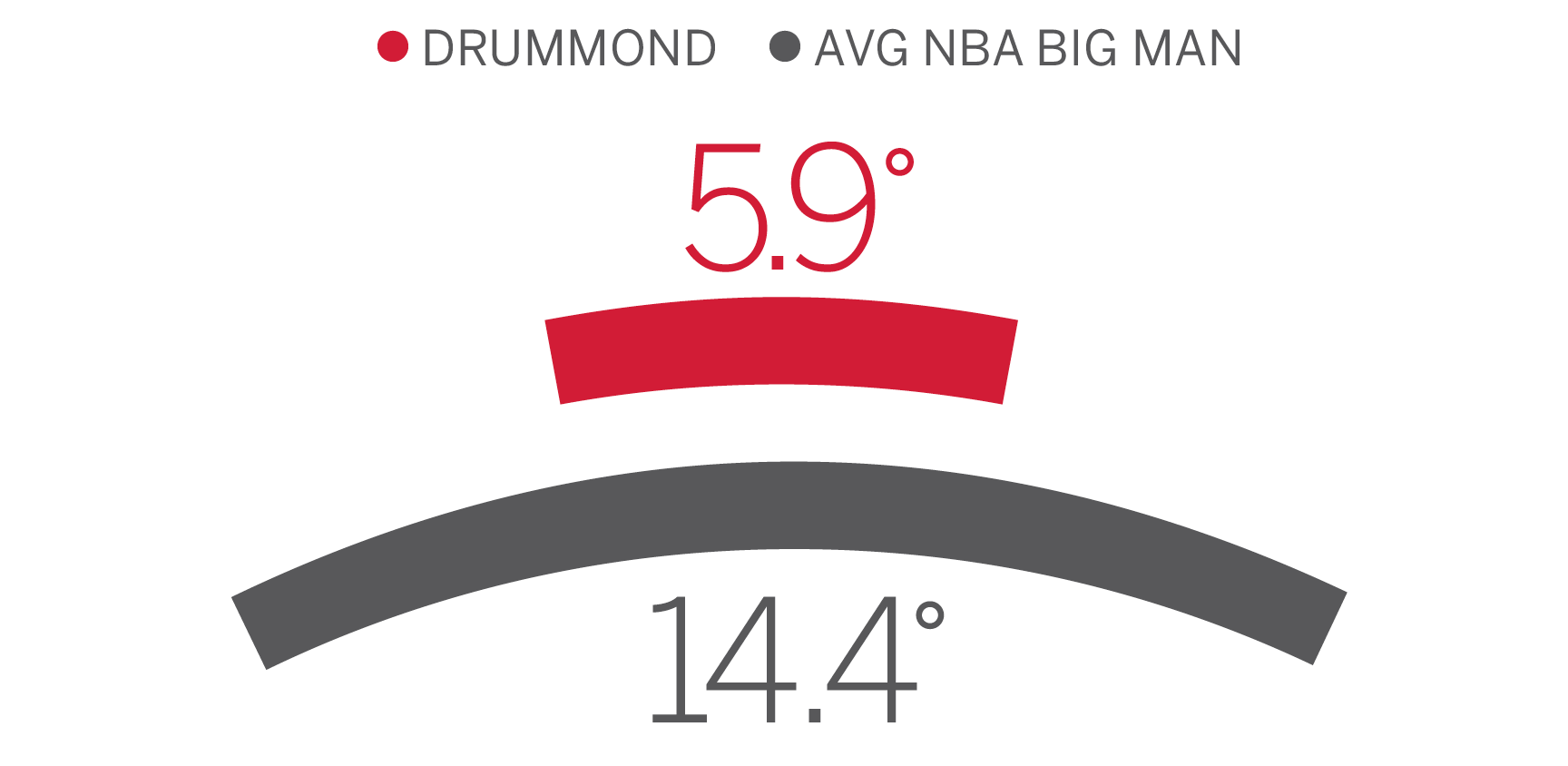

Working at peak efficiency

The orientation of Drummond’s hips and trunk differs by just 5.9 degrees as he moves laterally — almost 10 degrees less than your typical NBA athlete, regardless of position. This ability to control his center-of-mass allows him to react efficiently, and not waste movement (or time) with extraneous mechanics.

Even at just 22 years old, Drummond’s rebounding numbers are unmatched. This season, Drummond pulled down a league-leading 24.5 percent of all available rebounds while on the floor. He tallied a league-high 66 double-doubles this season, the most since, you guessed it, Howard notched exactly 66 double-doubles in 2010-11.

Indeed, it’s hard not to draw comparisons to Howard. The numbers don’t lie. In the past two decades, only one player has matched Drummond’s points and rebounding totals in his first four seasons in the league.That player? Again, Dwight David Howard.

It’s a name that has followed Drummond his whole career.

“I used to hear it a lot, but now it’s just like, I’m my own player,” Drummond says. “I can’t be compared to anybody else.”

THE HOWARD-DRUMMOND comparisons don’t stop there. Pull up Howard’s résumé and you’ll find remarkable durability in the first half of his career; Howard played every game of his first four seasons in the NBA, the only center to ever do that, according to Basketball-Reference.com.

Drummond has missed only one game due to injury in the past three seasons, a rarity for big men in today’s NBA. Van Gundy and the P3 staffers hope to keep it that way. The hard part — keeping his body in sync and movements symmetrical — is an ongoing process, requiring yearly check-ups in Santa Barbara to prevent the snowball effect.

“Our key is to not just make him more athletic or a better mover, but to keep his systems all go,” Elliott says. “If he has a small injury and he develops a compensation pattern, it’s not going to get by us. And it’s not because our naked eyes are going to see it; our technology is going to see it.”

Big men like Drummond are naturally more susceptible to injury simply because tiny abnormalities on long limbs can manifest into larger problems. Think about a standard pencil being harder to snap than one a yard long. Drummond’s clean bill of health isn’t pure luck, though randomness is very much a part of it.

Drummond’s left-to-right discrepancies are virtually nil, meaning one side isn’t consistently out-working the other, a red flag for breakdowns. During all double-leg testing, according to P3 reports provided to ESPN.com, Drummond’s asymmetry values fell well within their norms. The scariest, most common compensation pattern for big men is something called valgus, in which the knees clash together when they load to jump. Drummond, again, passes this test with flying colors.

“He can be as good as his ability to learn basketball,” Elliott says. “He’s got nothing holding him back to him being the best big man in the NBA, period. If we can keep him healthy, that’s the situation.”

Well, there’s one thing holding him back.

DRUMMOND MAY BE the best player at kicking off the game, but when it comes to finishing games, he’s often sitting on the bench. Why? The free throws.

Drummond is a physical marvel, but his Achilles heel, hitting free throws at a reasonable clip, has kept him off the floor in clutch situations. In Game 1 of the Pistons’ playoffs series with the Cavs, Van Gundy subbed Drummond out for Aaron Baynes with 2 minutes, 58 seconds left in the game.

And with good reason. Drummond just wrapped up with the worst free-throw shooting season in NBA history, at 35.5 percent.

The Pistons don’t track free throws made in practice, but Drummond says he shoots them “really good” outside of games. Van Gundy estimates his practice conversion rate at 65 percent.

The Pistons, with the instruction of famed shooting coach Dave Hopla, are trying to keep it simple for Drummond. As of now, Drummond says, he has not given thought to shooting free throws underhanded. Just three dribbles, pause and up — just as it has been all season.

Van Gundy understands all the mechanics in the world may not solve Drummond’s free-throw woes.

“For me, it was hitting a baseball,” Van Gundy says. “I really struggled hitting a baseball when I was younger. And we all know when you hit that ball, there are two things: There’s a physical component obviously — there’s something wrong I need to do better to hit the baseball better. But then, because you haven’t had success, it becomes a very big mental component too.”

Van Gundy admits he never did hit a baseball consistently, but he hasn’t resigned himself to the same fate for Drummond.

“I’ve had Shaq, Dwight and now Andre,” Van Gundy says. “It’s a hard thing made even harder by the fact that these guys are great athletes who are used to having incredible success, and then there’s one thing that they just don’t do well, and I think it seeps into their mindset.”

Van Gundy emphasizes that Drummond practices his free throws ad nauseum, and the notion that he just needs to practice more is “crazy.” Practice doesn’t make perfect, in this case.

“With these guys, look, they put in the effort to fix it,” Van Gundy says. “It’s just hard, for whatever reason, to translate from the practice floor to the game. Look, you’re standing there by yourself, with the game stopped and everybody’s watching. Let’s say a guy misses a jump shot, the play goes to the other end, and everyone’s focused on what’s happening there. But Andre’s standing there at the free-throw line, all everybody’s talking about who’s watching the game is his FT shooting. It’s hard. It’s really hard.”

“I mean, here’s this guy out there leading the league in rebounding and all he’s hearing about is his free-throw shooting,” Van Gundy says.

Beyond Shaq and Howard, bad free-throw shooters are commonplace among NBA greats. You don’t even have to look that far in Pistons history to find one. Four-time defensive player of the year Ben Wallace won a championship for Detroit during a season in which he made less than 50 percent of his free throws. Wilt Chamberlain won a championship and earned an MVP award missing more than half his free throws in 1966-67.

“He’s young and he’s got a lot to learn, but he has gotten better,” Van Gundy says. “We all, me in particular, want it quicker and all at once, so but that’s not usually the way it comes. It usually comes incrementally.”

Drummond turns 23 years old this August and, before that, the plan is to spend the summer at P3 once again. The status as the NBA’s best big man is there for the taking. Drummond just has to go up and get it. It just might take longer than he’s used to.